Articles

ESI: A proper Request for Production of Documents

Request For Production of Documents

Most attorneys structure their discovery tools to reflect the organization of claims, defenses, orders of proof, or other issues relevant to their legal theories and strategies. This structure is grounded in our knowledge of law and our unique ability to identify legal issues related to our comprehension of the facts of the matter entrusted to us by our clients. It would not surprise us that attorneys who practice in complicated patent cases need to develop discovery tools that reflect their understanding of the technical, scientific, mechanical, or electrical properties of disputed patent claims. Attorneys who litigate liability claims in the pharmaceutical field require discovery tools that reflect their sophisticated knowledge of chemical interactions, molecular biology, and other scientific fields. Indeed, attempting to practice in these technical areas without an understanding of the underlying science, probably leads to confusion and failure.

Recent case law and the amendments to the Rules of Federal Civil Procedure appear to require attorneys acquire a fairly sophisticated understanding of the manner in which information is electronically stored. Due to the ubiquitous use of computer technology, assisting a client to conduct a proper litigation hold or formulating effective discovery requests in a matter requires knowledge of the manner in which information is stored electronically on common sources such as computer hard drives. Attorneys with little or no knowledge of the manner in which electronically stored information (“ESI”) is created and stored have very little hope of crafting effective discovery of ESI.

Unfortunately, attorneys who wish to maximize the use of Electronically Stored Information (“ESI”) in their cases face several challenges. They need a definition of ESI that includes the different types of information stored electronically that are discoverable or will lead to discoverable information. They need to structure discovery tools that identify relevant, nonprivileged discoverable ESI and that also allow them to measure the effectiveness of a party opponent’s response to discovery. Finally, they need a paradigm that helps them understand the data types and sources of ESI resident on electronic media that they can use to maximize the likelihood of obtaining all discoverable information while laying the foundation to compel the disclosure of facts wrongfully withheld. This paper is an attempt at creating such a definition of ESI: a definition that reflects the technological realities of ESI while giving attorneys guidance in organizing their requests into relevant content and artifact data.

In order to appreciate the challenge of drafting a Request for Production of Electronically Stored Information, an attorney must understand two essential concepts:

(1) ESI is one or more of the following data types: file name, content, metadata, file system, application or operating system; and

(2) ESI is written to electronic media simultaneously by four discrete sources: end users, file systems, operating systems and applications. This article assists attorneys to understand the differences between the types of ESI and to craft a Request for Production that includes all data types created by all discrete sources.

I. A Technical Paradigm Describing Types of Data

a. Content and File Name Data; Metadata

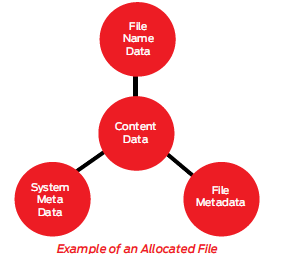

A typical computer file has a multi-part structure: file name, content, and metadata. Each part of the file’s structure is treated by the computer as a separate, distinct data type; but all the parts must be present for the data to have a “file” structure. In order for an operating system or application to access, read, or change the content data of a file, the content data must be linked to the file name and metadata parts of the file.

Content data that is linked to a specific file name is “allocated” to that specific file name. All allocated Content data is visible to an end user and is generally referred to as “active files”. Attorneys and most lay persons are familiar with content allocated by file name. This is the type of information that attorneys have traditionally requested to be produced in litigation. It includes memoranda, letters, spreadsheets, etc., that contain content which relates to a claim or defense of a party. A party can obtain this type of information by searching the file names or content of active files resident on a relevant computer. When conducting this type of search, however, care must be taken to avoid accessing the Content data in such a way as to change the “Last Accessed” metadata.

Content data that is linked to a specific file name is “allocated” to that specific file name. All allocated Content data is visible to an end user and is generally referred to as “active files”. Attorneys and most lay persons are familiar with content allocated by file name. This is the type of information that attorneys have traditionally requested to be produced in litigation. It includes memoranda, letters, spreadsheets, etc., that contain content which relates to a claim or defense of a party. A party can obtain this type of information by searching the file names or content of active files resident on a relevant computer. When conducting this type of search, however, care must be taken to avoid accessing the Content data in such a way as to change the “Last Accessed” metadata.

Content data that is no longer linked to a specific file name is “unallocated” data. When a file is deleted, the links between the content data, metadata, and the file name data are broken. Although the content data, metadata, and file name data are still resident, discretely, on the media after deletion, these data reside independently of one another. This data, therefore, no longer has a file “structure” and is invisible to the end user. The content data, metadata, and file name data, however, can be retrieved and examined simply using software that reads all data, regardless of whether the data has been linked to specific file name data. Moreover, special forensic software can “re-allocate” content data to its original file name and thereby “undelete” the file.

Because deletion does not eliminate the Content Data, many end users purchase software programs that eliminate Content Data by overwriting the content data with zeros or random data. These programs are generally called “wiping” utilities. It is interesting to note that when content data is overwritten by using a wiping utility, generally only the content data is affected. The space on the hard drive on which resides the content data that has been overwritten is available to store new information. Sometimes the unallocated space is used to store new information created by an end user (such as saving files); sometimes the unallocated space is used to store new information generated by the computer operating system or file system.

Metadata is electronically stored information that is a part of a file’s structure and is linked to file name and content data. Some metadata may be created by an end user, such as the comment metadata linked to a word document. Other metadata may be created by an application, such as the camera information recorded by programs that transfer images from digital cameras. Still other metadata is created by the file or operating system, such as creation dates of content data.

b. Content Data, File system and Application data; Operating System Data

Content data can be stored on electronic media in different ways. File systems are the organizational structures, rules, and principles which are used to organize content data. Different file systems have different file structures, rules and principles by which the file system organizes content data. Content Data becomes a “file” when the data is organized in accordance with a particular file system’s rules. NTFS, for example, is the file system underlying Windows. A file system’s organizational structure can be compared to the Dewey Decimal system used to organize books in a library; a file’s organizational components can be compared to a card catalogue that contains the file name data and metadata (data when a book was stored in the library for the first time, author, when the book was written).

Content data is not the only discoverable and relevant electronically stored information that attorneys must consider. In addition to content data (and its associated file name and metadata), an attorney must consider the Electronically Stored Information that records the manner in which computers and other devices have been used. Generally speaking, the manner in which computers were used in a case is determined by interpreting Application and File System data and by interpreting Operating System data.

Application data allows an operating system or program to run more efficiently. Generally application data is not essential to the storage and retrieval of any of the data types; however metadata related to application data may be very important in a case. For example, application data created before a change to a file system’s metadata occurs (termed “journaling”) may record recent changes that are relevant to a case or matter.

File System data and Operating System data may be very important in a case. Basically, these sources of data record the actions of end users when using the computer. Operating System data includes System Registry data, analysis of which can easily identify sources of discoverable information that have not been produced; mass deletion activity caused by wiping utilities; custodians of discoverable information that have not been identified; and a wealth of information that is used to identify who knew what, and when did they know it.

II. Who/What is creating Electronically Stored Information

Everyone understands that an end user can create content data and store it as a named file on a computer hard drive. The file system used on the particular computer organizes the content data by linking the content data to several metadata files and to specific file name data. The file system metadata files are created automatically and usually without any input or knowledge of the end user. Some metadata files automatically created include the time and date stamps of the creation of the file in this file system.

Operating systems and applications also automatically create data as essential features of their functions. The Windows XP operating system automatically creates and stores in the “System Registry”, substantial data regarding the software and devices connected to a computer. System Registry analysis identifies the existence and/or use of data deletion utilities, concealment of hard drives and external storage devices, and the manner in which a computer has been used during relevant, critical time periods.

III. Strategic considerations

The types of Electronically Stored Information and the Sources that create ESI can be graphically displayed in a table as set out in Appendix A.

Almost all Requests for Production of Documents have traditionally been limited to File Name and Content data created by End Users. With the advent of articles about “e-discovery”, some attorneys have included metadata created by the file system (Modified, Accessed, Creation dates). Traditional e-discovery vendors that process active files generally only process content and metadata created by end users. The result of this type of processing is large batches of active file types, but absolutely no deleted content nor any relevant evidence of the manner in which key players used their computers. Finally, because attorneys generally do not know of the existence of the other data types or sources of data creation, valuable, discoverable data created by the file system, operating system or applications is rarely requested.

In addition to recognizing the existence of ESI data created automatically by non-end-user sources, an attorney seeking ESI ought to strategically recognize that ESI will, initially, be produced by a party opponent. Based upon experience and case law, this author assumes that an RFP seeking production of the hard drives and electronic media in the possession and control of the responding party will not be compelled early in a case, on the ground that the producing party, using the client IT department or an expert of its choosing, ought to search electronic media in its possession or control for the information requested in the RFP. The challenge for attorneys is to create an RFP that reaches all types of data created by all Sources of ESI, which data is resident on the computers (or other electronic media) used by the key players in a case.

In order to draft such an RFP, this paper suggests that ESI must be:

(a) defined to reflect technological characteristics of electronic storage devices (such as computer hard drives), and

(b) described by category and item with sufficient particularity to force the producing party to search and produce relevant content and artifacts, or explain its failure to do so.

It is suggested that attorneys consider the following definition for use in their RFP:

Electronically Stored Information:

information stored in a medium from which it can be retrieved and examined , including information that is stored by an end user, application, operating system or file system , and includes file system data, content, metadata, file name data, application data and operating system data . “ESI” includes data of any type, in any format, including data resident at any physical location on any type of electronic media, regardless of the “logical” characteristics or properties assigned to the data by any operating system or application, including any data from which intelligence can be perceived with or without the use of any detection devices, software programs, applications, devices, file systems, or operating systems, including devices, programs, applications, file systems and operating systems other than those presently used or available to defendant to interpret data on electronic media. ESI includes, without limitation, user-created data such as word processing documents, spreadsheets, graphics, animations, presentations, email and attachments, audio, video and audiovisual recordings, and voicemail that are related to a claim or defense of a party, or which identifies a person or thing that is, in turn, discoverable.

Specifically, “ESI” includes:

A. data resident in the following areas of any electronic media:

1. file and RAM slack areas

2. unallocated areas of electronic media

3. swap file areas

4. allocated areas of electronic media, and

B. Data that identifies all the logical and physical characteristics of all data produced in response to this request, including but not limited to:

1. File modification, access, and created date and times

2. Sector location at which the data exists

3. Identification of the electronic media on which the data is resident.

Requests for Content:

Please produce in native electronic format (except for those items listed below) all electronically stored information related to the following items or categories. Please see the definition of ESI above, and note that this request includes content and associated metadata such as creation, Last Accessed, Modification dates, deletion status, and the identification of all computers on which data resides:

(This follows the traditional RFP in which content is requested in categories that relate to claims and defenses of the parties. The choice of format is a technical issue that is beyond the scope of this paper).

Request for Artifacts:

Please produce in native electronic format the following electronic information for each of the computers searched in response to this Request for Production of ESI. Please extract and copy this information using protocols that do not modify any of the content or metadata. It is suggested that respondent create a forensic copy of each of these sources of discoverable information to avoid spoliating relevant metadata:

A. The System Registry, if any, of the Operating System for each computer searched for ESI;

B. The Windows System Event Logs;

C. The Windows Prefetch Folder;

D. [Other Sources of Artifacts as discussed with Client IT or expert]

This definition of Electronically Stored Information is designed to capture both content and artifacts resident on electronic media that are relevant to the matter or that will lead to discoverable information. Content is usually that information, created by a human being, which is within the scope of discovery as defined in Rule 26(b). Artifacts are usually electronically stored information created by an application, operating system, and/or file system, and which are discoverable under Rule 26(b) as the “existence, description, nature, custody, and location of any…[ESI], documents, or other tangible things”. Artifacts generally are used to identify computer usage issues; for example, identifying additional hard drives installed by a party into one or more computers, but which drives were not disclosed or searched as a source of discoverable information.

The definition of ESI above includes information that cannot be produced using only the operating system and installed programs of a party’s computers. For example, the definition of ESI includes artifacts that identify whether a responsive file had been deleted, the date of deletion, and whether the entire file still exists, intact, on the party’s computers. Other ESI artifacts might include relevant metadata about a file. Using this definition of ESI, therefore, ought to trigger the issue whether the responding party has the ability and competence to properly produce the ESI requested. This, in turn, may lead to objection on the ground that the ESI request is overbroad, disruptive, burdensome, etc. These objections are properly addressed in a motion to compel. Substantial benefits can be had in identifying the data types that the responding party either does not have the capability to produce (and consequently is not preserving) or simply refuses to produce. By rationally relating each type and source of ESI to issues in a case, a Requesting Party ought to be able to obtain substantially all ESI in a case, including evidence of spoliation, other media, and other sources of discoverable information. Early resolution of these issues is also necessary to implement an efficient, rational discovery/production plan. ◊

FOOTNOTES

1 This article assumes the requesting attorney desires to request discoverable content and artifacts. Counsel could, of course, agree to litigate the case with only the information the producing party is willing to provide. For example, before the amendments to the federal rules, it was common for attorneys to litigate cases without obtaining relevant, discoverable, deleted content. Whether attorneys can continue to ignore relevant content and artifacts is an area of developing case law and beyond the scope of this article.

2 In this regard, an RFP can be analogized to the inverse of a litigation hold. Where a litigation hold identifies and preserves all sources of discoverable ESI, an RFP forces the production of all discoverable ESI; however, the RFP is more difficult to construct because the RFP must be executed by the party opponent and because the Requesting Party cannot easily dictate a process or protocol to follow.

3 This is a “definition in progress”; as changes are made, they will be posted to the Vestige website: www.vestigeltd.com

4 This phrase is included in Committee Note, Rule 34, Amended Rules of Federal Civil Procedure, 2006.

5 These are the operators that may write data to electronic media.

6 These are the organizational categories of Electronically Stored Information in a paradigm file system. See Brian Carrier, File System Forensic Analysis, Chapter 8 page 174

7 This list is suggested in Civil Discovery Standards, American Bar Association, August 2004 Amendments.

8 To properly identify artifacts, you may need to have completed formal or informal discovery of the data architecture and data process flow of the producing party. You may need the assistance of your client’s IT department or outside expert to formulate an understanding of this data architecture and to properly craft the Request for Artifacts.

9 Rule 34(b) requires RFP to identify with reasonable particularity the items or category of items to be produced. This request identifies categories of artifacts.

This definition of Electronically Stored Information (ESI) is designed to capture both content and artifacts resident on electronic media that are relevant to the matter or that will lead to discoverable information. Content is usually that information, created by a human being, which is within the scope of discovery as defined in Rule 26(b). Artifacts are usually electronically stored information created by an application, operating system, and/or file system, and which are discoverable under Rule 26(b) as the “existence, description, nature, custody, and location of any…[ESI], documents, or other tangible things”. Artifacts generally are used to identify computer usage issues; for example, identifying additional hard drives installed by a party into one or more computers, but which drives were not disclosed or searched as a source of discoverable information.

The definition of ESI above includes information that cannot be produced using only the operating system and installed programs of a party’s computers. For example, the definition of ESI includes artifacts that identify whether a responsive file had been deleted, the date of deletion, and whether the entire file still exists, intact, on the party’s computers. Other ESI artifacts might include relevant metadata about a file. Using this definition of ESI, therefore, ought to trigger the issue whether the responding party has the ability and competence to properly produce the ESI requested. This, in turn, may lead to objection on the ground that the ESI request is overbroad, disruptive, burdensome, etc. These objections are properly addressed in a motion to compel. Substantial benefits can be had in identifying the data types that the responding party either does not have the capability to produce (and consequently is not preserving) or simply refuses to produce. By rationally relating each type and source of ESI to issues in a case, a Requesting Party ought to be able to obtain substantially all ESI in a case, including evidence of spoliation, other media, and other sources of discoverable information. Early resolution of these issues is also necessary to implement an efficient, rational discovery/production plan.